Maksimilijan Vanka: a life fit for a novel

Vanka's large and diverse oeuvre has been insufficiently researched in Croatian (and it would also seem American) art history, whereas to the general public he is relatively unknown. This is usually justified by the fact that in leaving his homeland, the artist's work had been lost for us; a claim which has been firmly refuted by Tonko Maroević in one of the reviews of the retrospective exhibition of Vanka's works held in Klovićevi Dvori Gallery in the early 2000s, some seventy years after his last major solo exhibition held in Croatia. He noted, as a matter of fact, that Vanka never completely severed the ties with “his old country” and that the features which he incorporated in the Zagreb environment, either as a student of Bela Csikos-Sesia (and a sort of companion of the Zagreb Colourful School), or as a co-exhibitor of the famous ‘Group of Three’, i.e. a stylistically similar fellow artist of Ljubo Babić, Vladimir Becić and Jerolim Miše, were represented in his ‘American phase’, which includes a range of “minute segments and various aspects dealing with motif, problem and style”, just like the Croatian one (comparable in both scope and meaning). Vanka was represented sporadically through a few works from domestic collections, in thematic exhibitions in his homeland (e.g. Watercolour art of the 20th century in Croatia, 1958; Self-portrait in Recent Croatian Painting, 1976; Still Life in Recent Croatian Painting, 1979; Expressionism and Croatian Painting; Human Figure in Recent Croatian Painting, 1982), and two smaller exhibitions of his works from the holdings of Croatian museums and from private collections were held (Exhibitions from the Gallery Holdings. Maximilian Vanka, 1976; Maximilian Vanka. Portraits, 1997). Occasional newspaper reports from the New World during his lifetime, as well as the headlines accompanying the later opening of the Memorial Collection in Korčula, bear witness that there was a certain interest in the artist’s fate. Although the contributions (albeit unequal in scope and differently focused) of Vladislav Kušan, the threesome Cvito Fisković – Vinko Zlamalik – Ljerka Gašparović (1968), Zdenko Rus (1976), Ljubo Gamulin (1987), Snježana Pintarić (1997), Ivo Šimat Banov (2002) and the aforementioned Maroević (2002) right down to the most recent additions by Ana Šeparović (2016) and the tandem Jasminka Najcer Sabljak – Silvija Lučevnjak (2018), are commendable in the overall examination of his work, the fact remains that Vanka has never been adequately monographically presented. According to critics, the aforementioned ambitiously designed retrospective in Klovićevi dvori by Nevenka Posavec Komarica did not result in the desired synthetic overview, despite the fact that it, together with a somewhat earlier and more studiously arranged, small exhibition at the James A. Michener Art Museum, which in turn included Vanka's works from that museum and some, mostly private, American family collections, did provide a broader insight into his oeuvre, and it familiarised Croatian audiences with hitherto unseen works created in emigration. Not long thereafter, Nikola Vizner, who participated in preparing the American exhibition, defended his doctoral dissertation, which was the first somewhat complete and systematic cross-section of Vanka's 50-year activity, and whose special contribution is outlining the artistic context that Vanka encountered coming to study in Brussels, as well as a more informed analysis of American artistic circumstances at the time when the artist first settled on the East Coast in the mid-1930s. It is undeniable, however, that Vanka's work still eludes a comprehensive analysis, which would, apart from emphasizing amongst critics undisputed outbursts of excellence – early landscapes with borderline expressionist aesthetics, more successful portraits of diverse stylistic attributes, and cycles of more luminous landscapes from the early 1930s akin to Babić – take a more sober look at his entire body of work; on the one hand more appropriately “placing within our evolutions” certain sections; and on the other hand discerning the “creative thread” which, in Gamulin's words, “indeed does run successfully, albeit with difficulty, through his entire body of work” from the ballast of confabulation and superfluous ‘arranging’, for which Vanka is usually criticized. Šimat Banov assessed him as a “painter of unstable and short-lived preoccupations, methods and solutions, of a broken artistic existence” who nevertheless left several dozen works that “can be incorporated within the good tradition of Croatian modern art”. Maroević, in his characteristically more benevolent tone, pointed out the “great disparity between his potential and orientations, with almost the only common denominator being his considerable manual skill and morphological nomadism”, his propensity to “vent by means of technical virtuosity in skillful exhibitionism, in captivating stylization and in the theatricality of the models' poses”, his artistic personality in the extremes between “fashionable production reminiscent of saccharine academicism” and “several attempts at ‘abstract’, post-cubist composing”, which is why the “focal point of the oeuvre” should be sought somewhere in the middle. It is generally believed that this is an artist who is “not a simple case”, who is “a problem for our critics” and “a questionable figure of our art”.

Too often, therefore, when trying to evoke Vanka's work, more attention had been paid to his peculiar appearance and dramatic personal biography – “fate fit for an adventure novel”, according to Šimat Banov – especially his unexplained ancestry and ostensibly mysterious death in the Pacific waters of Mexico. The exception is the above-mentioned dissertation, which approaches Vanka's curriculum vitae much more seriously. It summarizes several variations of the fundamentally identical assumption about the artist's birth being the result of an extramarital affair within the circles of the (high) Austro-Hungarian nobility, noting that the romanticized biography of Vanka, The Cradle of Life (1936), written by the painter's American friend, the Slovenian Luj Adamič, who wrote about him in several literary and journalistic texts, largely contributed to the widespread lore.

Vizner himself often resorts to the same novel as a source, questioning, however, its credibility with information from documents preserved in the Vanka family archive. The Register of Births of the Zagreb Parish of St. Mark includes a record of the birth of Maximilijan Joseph as an illegitimate child. The father's name is omitted, while the mother is listed as Katarina Vanka, a private citizen, with a residence in Brno, Moravia. The child's godmother was the midwife Marija Salavari. The Registers thus refute the popular hypothesis percolating through a number of texts on Vanka’s ancestry: that he chose the surname himself to emphasize that he was an abandoned child or that he acquired it as a derogatory nickname for the same reason. Vizner correctly deduced, however, that this information is not conclusive proof that it was indeed the mother's true surname. While investigating the circumstances of the painter's death, the same author obtained a copy of his death certificate from the Municipality of Porto Vallarta in the Mexican federal state of Jalisco, from which it can be seen that Vanka's allegedly unexplained drowning was immediately preceded by a heart attack. Just like Posavec Komarica, Vizner bases some of his conclusions on conversations with the artist's living relatives and acquaintances, who, nonetheless, were not a completely reliable source of information. The reason for this is the deceitfulness of memory, along with the fact that these are, after all, second-hand experiences and, lasty, that Vanka himself was often contradictory in his statements, as evidenced by a number of equally mutually contradictory archival documents. The most eloquent example of this are the records of the Lower Town's Boys' Folk School and the Royal Real Gymnasium in Zagreb. While they disprove, for example, the unsubstantiated claims of several authors that Vanka – having been raised by a peasant woman from Kupljenovo (Pušća County) near Zaprešić with the regular financial support of unknown benefactors – attended a primary school (at least for a while) in “Brestje”, where he, under the supervision of his guardian, ostensibly lived in his own manor at the same time, they are teeming with inconsistent and evidently made-up information that varies from year to year in the sections about the students' family circumstances. Hence, the assertions about Vanka's place of birth, class affiliation and his mother's residence do not coincide; moreover, it is particularly bizarre that individual school years of the gradebook include information about the name and occupation of the alleged father, which are, as expected, in discrepancy. We learn from the school General Registers that Vanka's schooling in Zagreb didn’t start until 1898/99, after he attended the first two grades of folk school elsewhere, which is concordant with the claims of a local history chronicler from Zaprešić that the boy's name was recorded in the main gradebook of the elementary school in Pušća in 1896. Anton K(r)menth from Brezje near Samobor, who is probably the same person as the lord Kment(h) from Brezje in the then Municipality of Rakov Potok, is recorded as his guardian on two separate occasions in the high school Matriculation Records. Due to the current unavailability of more credible arguments that would confirm this assumption, on this occasion it remains only an intimation. The person occasionally appearing in the role of the guardian or “resposible supervisor” is Jozefina Rieger, the widow of a postal clerk, with an address at Ilica Street 96, who is, incidentally, as Vanka's landlord, the only constant reference in the school gradebooks and, later, student directories, until he came of age.

Having graduated high school in 1908, he spent the next three years attending the Provisional College of Arts and Crafts, while simultaneously, in his own words, attending the Faculty of Philosophy for a few semesters. In the Archives of the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb there is a record of Vanka as a student of a beginner course of the Department of Painting, from which it is evident that he was taught the main subjects by Bela Csikos Sesia. It is worth emphasizing that the preserved material does not include Vanka's degree certificate, which, according to the head of the Archives, could lead to the conclusion that he had never officially finished his studies in Zagreb. In the fall of 1910, as a “boarder of the temporary art school in Zagreb” who had been intending to go to Brussels in order to “perfect himself in the field of art”, he was heard before the competent authority of the City Government in order to determine his domicile and regulate his military service obligation. All the steps taken by the city services, including contacting the Magistrate in Brno, were futile, which is why Vanka was eventually included in the conscription lists of conscripts of a dubious domicile. He was only granted his domicile right in Zagreb six years later, and this was based on his many years of continuous residence in the city, whereby the prerequisites for acquiring Hungarian-Croatian citizenship were fulfilled, at least until “he was proven other / foreign / citizenship”.

Critics agree that in Vanka's early works – mostly nude and portrait studies, vases with flowers, charcoal sketches, watercolours and a few oil paintings, created as part of compulsory student exercises – raw talent is evident. Referring to several works created around 1910 and presented at the exhibition from the early 2000s, Maroević assesses that with them Vanka is “amalgamating himself into the genealogy of Croatian Modernism, partly putting to good use the experiences of the ‘Colourful school’, and partly – that is with paintings inspired by forest scenes – opening up the possibilities of a more liberal understanding of smudges and colour, that is, the creation of an almost autonomous space of the painting”.

From autumn 1911 to summer 1914, Vanka studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and the School of Decorative Arts in Brussels. To what extent this, for local artists unorthodox, choice of destination for the continuation of his education was conditioned by the need for broadening his horizons in an at the time already established cultural-artistic centre, and to what extent by practical motives, including alleged family and financial reasons, we can only speculate. In the context of the oft-repeated claims in literature that he took up residence there thanks to generous family support, it should be mentioned that during all his academic years he received scholarships from the Provincial Government of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia, on different grounds and in various amounts. During that period, his modest Brussels financial circumstances, as well as the necessity of constant financial support for the young ward so that he would be able to merely continue his studies in Belgium, are referenced in several documents of the Department for Social Welfare of Zagreb (Croat. Sirotinjsko povjerenstvo), under whose supervision as an illegitimate child Vanka had been since birth. One archival source from 1912 bears witness to a travel grant that Vanka was awarded for visiting the museums in Antwerp, but he most certainly extensively pored over collections in other nearby culturally relevant centres as well. He intensively studied the old masters, not remaining mute to the diverse contemporary forces in the artistically vibrant atmosphere of his new environment. Vizner points out that in Brussels, where in addition to Belgian artists, who were themselves active on the artistic map of Europe, French, German, Dutch, Spanish, British and, for example, Swiss artists also exhibited, “the influences of Impressionism, Symbolism, Art Nouveau, Pointillism, Post-Impressionism, Proto-Expressionism, along with the new Parisian movements of Fauvism and Cubism, the British Arts and Crafts movement and its Art Nouveau derivations, the Pre-Raphaelites, as well as the idea of ‘art for art's sake’ of the Aesthetic Movement converged”. At the High Master's School, Vanka attended “several courses in drawing based on live models and a 1st year course in decorative painting” and received “one honourable mention for a drawing composition and a first prize for a decorative composition in 1913– 1914”. In his own words, he was instructed by the renowned professors Constant Montald (1862 – 1944) and Jean Delville (1867 – 1953). Although a skillful draughtsman himself, with a refined sense of colour and composition, Delville, as a representative of the aesthetics of idealism, favoured content over form, considering art to be merely a means of achieving higher spiritual and moral goals. Inclined towards the mystical, with his allegorical symbolism – in the words of Snježana Pintarić, of a Wagnerian-Moreauian expression – he influenced the young Croat, thereby building on the symbolist-secessionist heritage that Vanka had brought with him from his Zagreb studies.

In Croatian museums and private collections, dozens of works created during his student-day wanderings across Belgium and the Netherlands have been preserved: city vedutas and Dutch interior paintings, the odd portrait (for example, the portrait of an old woman from Volendam, Geertje Karregat, known as Zaligmaker – the Saviour – a kind of local attraction and a frequent model for artists), small marinas in watercolour and pastel. One such, according to Grga Gamulin's appraisal, excellent, dark-toned watercolour, Skiffs - A Motif from Holland (1912), was bought at the exhibition of the Art Society in 1913 by the government's Department of Religion and Education and donated to the Academy for the Strossmayer Gallery, and is today part of the holdings of Zagreb's Modern Gallery. Vizner evaluates Vanka's Dutch interiors of a dark and dull palette (Loving Marriage, Dutch Interior, Dutch Women), with only the occasional white form as a light source, as a conservative academic style of painting, based on Dutch painting of the 17th century.

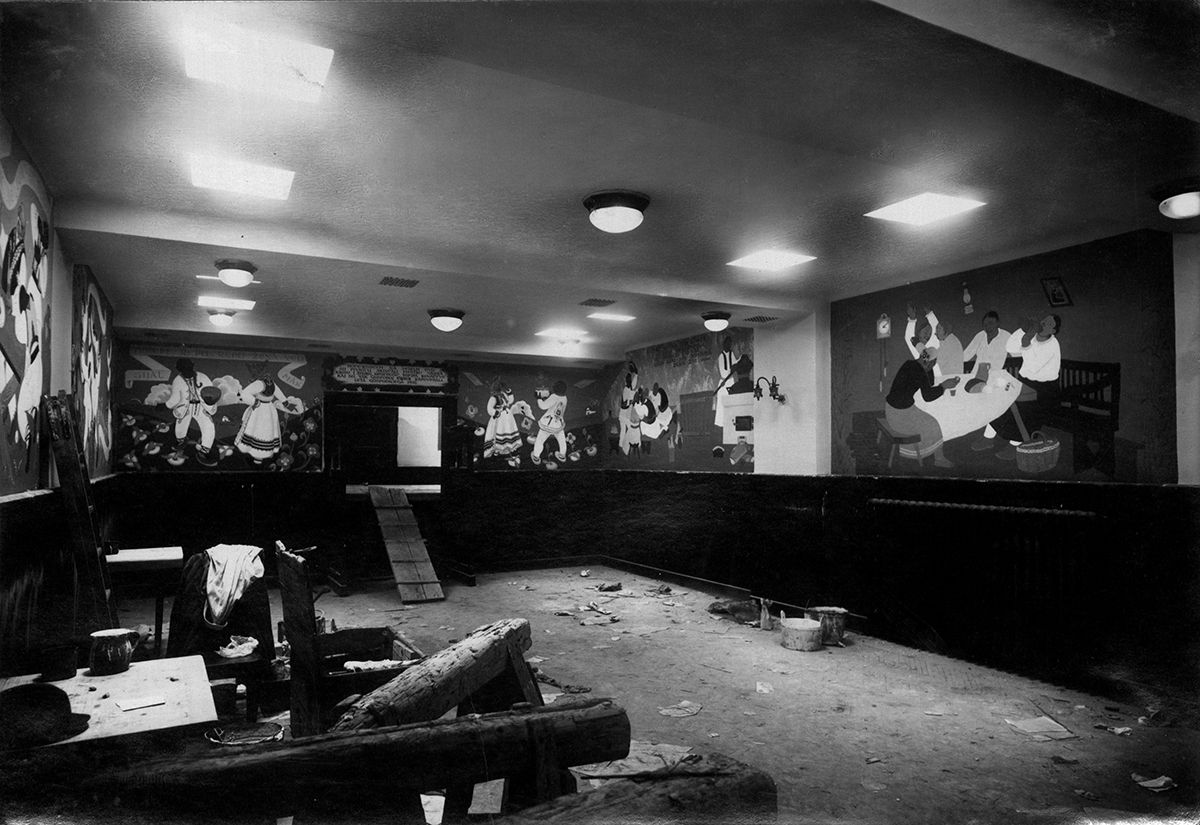

At the Brussels Triennial Salon in 1914 Vanka exhibited the painting The Fairgoers (Fête de la Madone en Croatie), which was awarded the gold medal of King Albert. In that earliest manifestation of Vanka's “folklorism impregnated with rustic piety”, as Maroević describes it, local critics already back then recognized the influence of contemporary Spanish painters. The Basques Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta – with his canvases of folklore motifs, darkened palette, figures with theatrical gestures and modelled like sculptures – and the thematically similarly oriented deaf-mute brothers Valentín and Ramón de Zubiaurre, the latter inclined to the simplification of form and volume, and the flattening of the picture plane, are usually mentioned in this context, along with, occasionally, the Catalan Hermenegildo Anglada.

Vizner expounds his view claiming that Vanka's paintings with depictions of peasants dressed in traditional garments, set in idealized landscapes of cultivated fields, with a white bell tower in the distance and a desolate cemetery at the edge of the valley, and the dignified focus of the depicted on a religious or an agricultural activity are the embodiment of “the artistic formula of romantic nationalism rooted in antebellum Europe of the late 19th and early 20th centuries”. In this context, Ivo Hergešić's thoughts are striking: “His favourite is Zuloaga, who has an influence on him, not artistically, but, so to speak, ideologically. Vanka - the regionalist, Vanka the ardent amateur of Croatian folklore, looks up to contemporary Spaniards because their example emboldens him to artistically exhaust ethnographic motifs harboured in his soul since his earliest childhood.” Birth and death, working in the fields, folk customs, beliefs and superstitions, the harvest festival, reaping and nuptials – as beautifully enumerated by Kušan – are the subject of a series of large compositions that Vanka created, with varying degrees of success, over the next two decades. The same critic, aware that in Vanka “the story is often too ‘arranged’ at the expense of the art”, points to a novelty brought to Croatian art of similar thematic preoccupations by his “attempts to epically depict the main elements accompanying or driving the life of peasants in decorative conception”. Moreover, Rus clearly defines this ‘new interpretation’ as “decorative steadfastness, the hectic heat of coloristic diversity consistently carried out in every square centimetre of the canvas without academic modelling and aerial perspective”, extending this to some of Vanka's later compositions (Under the old crucifix, Witches - Enchantment Against Hail), in which his constant tendency towards the mystical is clearly manifested. This thematic segment of the artist's oeuvre in the Korčula collection is represented by the two aforementioned works, along with another concurrent work, segment, which is characterized by a much softer modelling and a radically different treatment of light, which has its source within the scene itself. The painting supposedly illustrates an ancient Zagorje ritual in which, on Easter Eve in a secluded place in the mountains, some elderly women reveal to an unmarried local girl the identity of her future husband. In so doing, they cut her hair; when it grows back, her wish will come true; and in the meantime the young woman will be forced to stay at home. This way, she will preserve her light complexion, the ideal of peasant beauty. The girl pays for the service with chickens, bread, wine, milk and oil.

Several authors have pointed out that the same propensity for accentuating colour, the emphasis on its sonority and intensity (which Vanka inherited from his Spanish contemporaries), combined with the influence of the “general spirit of Art Nouveau stylistics”, can also be recognized in his contemporaneous landscape works, even those executed in watercolour techniques. Gamulin positions these watercolours, which are – in the words of Šimat Banov – “lighter by nature, under the influence of Spanish darkness became heavier due to full and strong volumes, and with the hard modelling of the forms became almost opaque”, on the border between Art Nouveau and Expressionism. Among the works of art that Vanka's family donated to the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in 1968, his earliest watercolours were not represented. About fifteen years earlier, however, the work Vinski vrh [Wine Peak] (1915) was purchased in the name of the Modern Gallery (at that time under the Academy's jurisdiction) from a local family collection, which, along with After the Storm and After the Rain, Gamulin underscores as excellent examples of “that unique moment of Croatian landscape art”. The Strossmayer Gallery owns a (in achievement) more modest watercolour from the same phase, Velić Village (1917), which arrived in the 1980s as a gift from Boris Lubienski, having been previously, it seems, owned by Ernest Schulz from a prominent Jewish family in Zagreb for whom Vanka, probably around the same time, also executed several portraits.

Portraits constitute the third important genre-based section of Vanka's oeuvre, with self-portraits being a significant subsection of it. The same variability of expression is also manifested in this segment of his artistic production. His earliest known self-portrait - St. Sebastian (1914/15) Maroević describes as “the fruit of unusual sophistication and extremely Decadentism-esque, ‘liberty’ stylisation and psychological characterisation”. In the first years after his studies, he created a series of Symbolist-Expressionist portraits and self-portraits in a characteristically expressive vein, of a darkened colour value scale with only a few ivory accents and imaginary background landscapes as an echo of the psychological state of the person portrayed. Self-Portrait (1921) should also be mentioned here – according to Gamulin – a masterpiece of Vanka's “neo-romanticism”, where “the romantic can be seen in the general arrangement and the gesture”. Among his later works, Pintarić distinguishes the sporadic “worst variants of insipid ‘unpretentious realism’”, in which she classifies, for example, several pastels from the Modern Gallery (Bust of a Woman, Portrait of a Woman), from the occasional “intriguing” outcomes, such as the “neoclassical composition of ‘quasi-cubist shapes’” of the Portrait of the Hanžeković family. In his last creative phase, in portraiture, as well as in his landscapes, Vanka resorts to Van Gogh's painterly gestures and palette. The Korčula collection includes the Portrait of the Musician Emerich / My Friend the Musician (1915) from a group of acclaimed symbolist-expressive works and the already mentioned Self-Portrait (1921), which Šimat Banov draws as an example of “certain artistic opportunities that Vanka missed” (“He turned a deaf ear to Cézanneism, but the promises are visible in the details, so it can be assumed that in other, for the artist and the environment, happier circumstances, everything could have turned into an artistic-structural problem, rather than a narrative or folklore one”). It also includes considerably more conventional works, the pastel Portrait of a Girl with a Hat, and several sanguine paintings (Portrait of a Man, 1926; Portrait of a Woman with a String of Pearls, 1928; Portrait of a Woman Leaning on One Arm, 1932). Vanka portrayed a whole range of contemporaries in sanguine and such portraits were in high demand, although not all equally successful. Pintarić points out that in this technique he achieved the best effects with the theatrical placement of figures, a strong contrast between sequences of light and shade, and an emphatic gesture with which the chalk leaves a mark on the paper. In the Strossmayer Gallery holdings one can find Vanka’s Portrait of Zlatko Baloković, another in a series of skillfully drawn, but otherwise “unpretentious” sanguines, and since recently also a very interesting gouache Portrait of Vladimir Lunaček (1923), which, due to its expressive background colour and the motion of the portrayed body heralds the artist's early Zagreb portraits.

sadržaj nakon portreta

According to Vanka himself, at the beginning of the First World War as a member of the Belgian Red Cross, he experienced first-hand the horrors of the battlefield, which permanently marked him, strengthening him in his previously existing pacifist beliefs, and the scenes he witnessed reverberated through a series of his later artistic achievements with a strong anti-war message. He manages to return to Zagreb in the fall of 1915, allegedly forced to leave a large number of his works in Belgium, and already in November he holds his first solo exhibition in The Ulrich Gallery. He exhibited several of the aforementioned paintings of Dutch interiors, studies for several compositions whose titles (Melodia, On the Elysian Fields) allude to Symbolist tones, also a reproduction of the illustrious The Fairgoers and another large folkloresque scene, a kind of variant of it, several portraits and a series of Zagreb and Zagorje landscapes. The exhibition received considerable attention in the press, with essentially positive reviews from critics, who admittedly criticized him for the excessive influence of the French Impressionists and Spanish modern art, while at the same time praising his very successful landscapes in watercolour (Vinski vrh, After the Rain, Two Poplars, Marija Bistrica), the cycle for which Rus assesses that “to this day rightly counts as Vanka's crowning achievement”. While the portrait of Senator Taborski (The Portrait of My Benefactor) was negatively evaluated, the portrait of Vanka's former schoolmate and great friend, musician Mirko Medaković (My Friend the Musician), a fine work of “expressive style and shifted pose of the sitter”, is considered one of his best exhibited works..

As a consequence of that exhibition, Vanka became an active participant in the local art scene. He made friends with numerous painters and other artists, was a welcome guest in the salons of the affluent bourgeoisie, and, it would also appear, in certain aristocratic circles, for example at the Mihalović's, Pejačević's and Mailáth's. In August 1920, he was appointed teaching assistant at the Royal College of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, only to be promoted to an ‘assistant professor’ the following year, and in 1923 appointed full professor. He would be employed at that institution until 1936, and during that period he would teach students the evening nude, composition, drawing and fresco technique. It seems that one of the contributing reasons for Vanka's decision to permanently leave his homeland after a two-year stay in the United States of America was the inability to get a promotion to a higher pay grade because of a bureaucratic dispute with the State Council and the Ministry of Education in Belgrade, which did not recognize his higher education degree.

In the summer of 1923, Vanka participated in the ethnographic expedition to Pokuplje led by the curators of the Ethnographic Museum Vladimir Tkalčić and Milovan Gavazzi, and six other participants joined them, including the painter and woodcarver Srećko Sabljak. During that one month, rowing downstream from Karlovac to Sisak, they visited dozens of villages, where they explored the local ethnographic and architectural heritage. On that occasion, Vanka made a series of sketches, drawings and paintings on paper, recording local architecture, country house and chapel interiors, as well as landscapes. These experiences gave rise to the exquisite watercolours Motif of Kupa near Petrinja (1923) and Cerje on Kupa (1923), which Gamulin assesses as the pinnacle of Vanka's “uptrend line”, which began with a series of landscapes from the Zagreb area exhibited in the Ulrich Gallery in 1915.

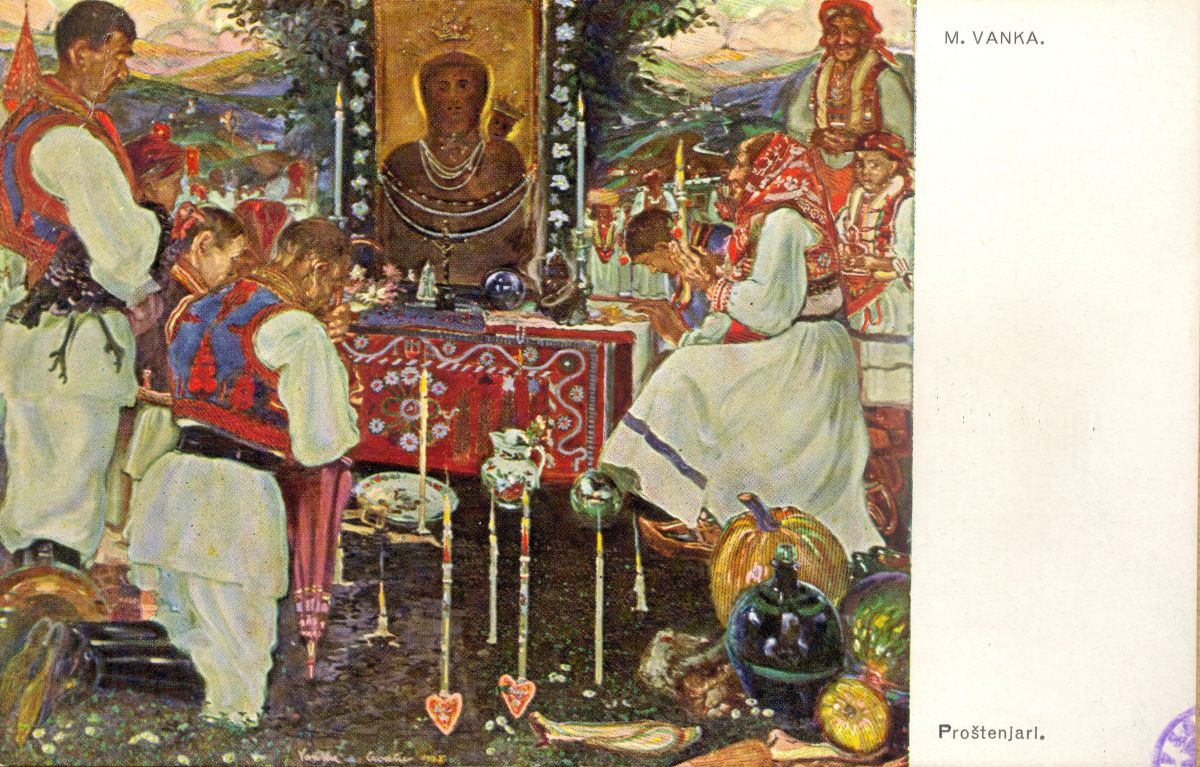

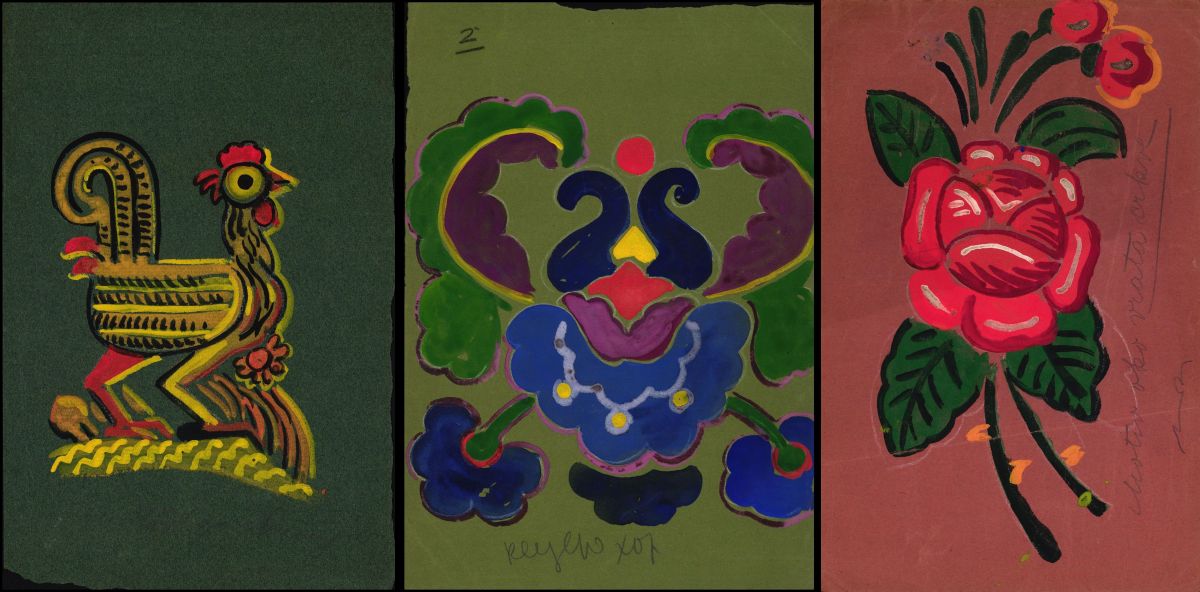

Vizner writes that during the expedition, and probably subsequently, Vanka collected a solid collection of folk handicrafts, above all embroidery and parts of folk costumes, which he used abundantly to draw inspiration in his works of ethnographic subject matter. Thus, while working on the stage and costume design for Krešimir Baranović's ballet The Gingerbread Heart [Croatian Licitarsko srce], which was staged the following year at the Zagreb Croatian National Theatre, he used, among other things, motifs from the Pokupsko folk costume. In the Memorial Collection, a hitherto unidentified sketch for scenic design is preserved, while in the Croatian Academy's Division of the History of the Croatian Theatre one can find somewhat more material related to this Vanka's engagement, mainly the elaboration of stage and costume design details derived from the stylization of folklore motifs.

Vanka's stage design for Baranović's ballet, as part of the Yugoslav section dedicated to artistic crafts, theatre and education, was exhibited at the great International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris (Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes) in 1925. It is worth noting that Tkalčić played an important role in the preparation of the Croatian part of the exhibition, along with Tomislav Krizman and the then manager of the Museum of Arts and Crafts, Gjuro Szabo. At the same exhibition, Vanka was also represented within a section in the National Pavilion, as the author of an art template with folklore motifs for three stained-glass windows executed by the glass painter Ivan Marinković.

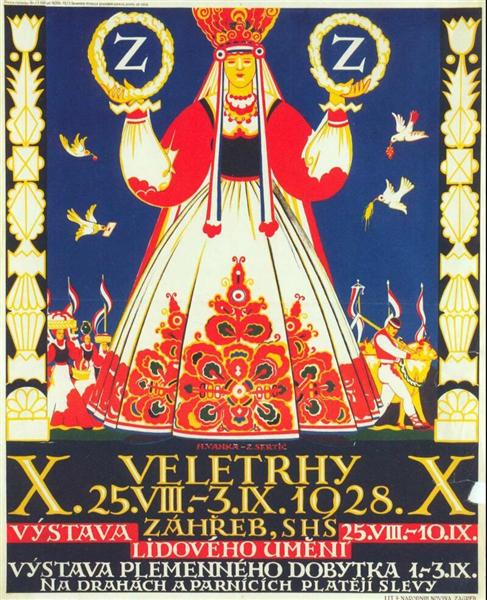

The Korčula collection includes two sketches in tempera with depictions of male and female figures in folk costumes by an ox cart, which until now, interestingly enough, had not been recognized as templates for the poster for the X. Zagreb Fair in 1928, designed by the painters Zdenka Sertić and Maksimilijan Vanka. It is also worth mentioning that as part of the accompanying Exhibition of Folk Handicrafts, the ethnographic collection of Mrs. Maksimilijana Mogan was exhibited, which also included Vanka's painting (!) “letting us in on a wedding secret”, A Bride's Preparation for the Wedding (1925), now owned by the City of Zagreb.

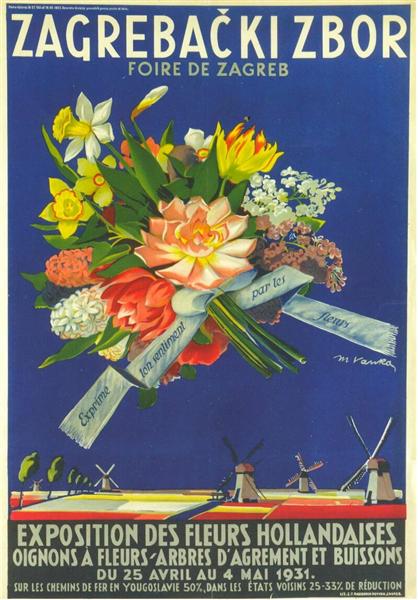

Vanka repeatedly tried his hand at designing exhibition posters: for example, there are preserved examples of the poster for the Exhibition of Croatian Artists (1916) and the Lada Exhibition (1920), the latter in two variants, and the much later Zagreb Fair - the Exhibition of Dutch Flowers, Bulbs, Ornamental Trees and Shrubs (1931). We also know that he was involved in book illustration (M. Feldman, Behind the Sun, 1920; T. Prpić, Azure Moments, 1920; D. Prohaska, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky: A Study of a Pan-Slavic Man (1921); I. Horvat, The Sounds of Solitude, 1925) and the design of postcards and greeting cards. In New York in the 1930s, he designed dance costumes for the ballerina Mia Čorak Slavenska, playing around with the motifs of Croatian folk costumes anew, as well as the costumes for the four roles played by prima donna Zinka Kunc at the renowned Metropolitan Opera House.

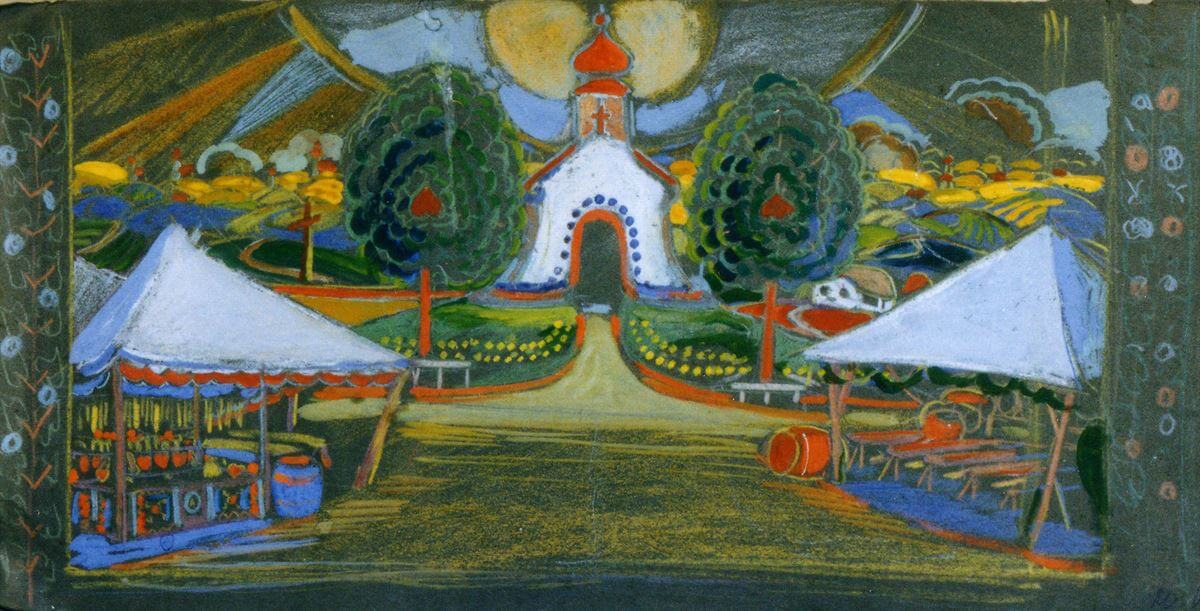

Vanka's interest in folklore traditions and folk customs also remained evident in the mural created in 1932 in the canteen of the Zagreb City Wine Cellar with his associates and assistants Krsto and Željko Hegedušić, Edo Kovačević and Kamilo Tompa. In contrast to Krsto Hegedušić's portrayal of rural everyday life with an emphasized social component, Vanka paints folk customs and festivities in an ornamental-decorative manner, illustrates verses of folk songs, etc. Marina Bagarić considers his approach to the reinterpretation of folk heritage as a manifestation of “‘our expression’ of the painter-‘citizen’, with a focus on the purely artistic qualities of the work”.

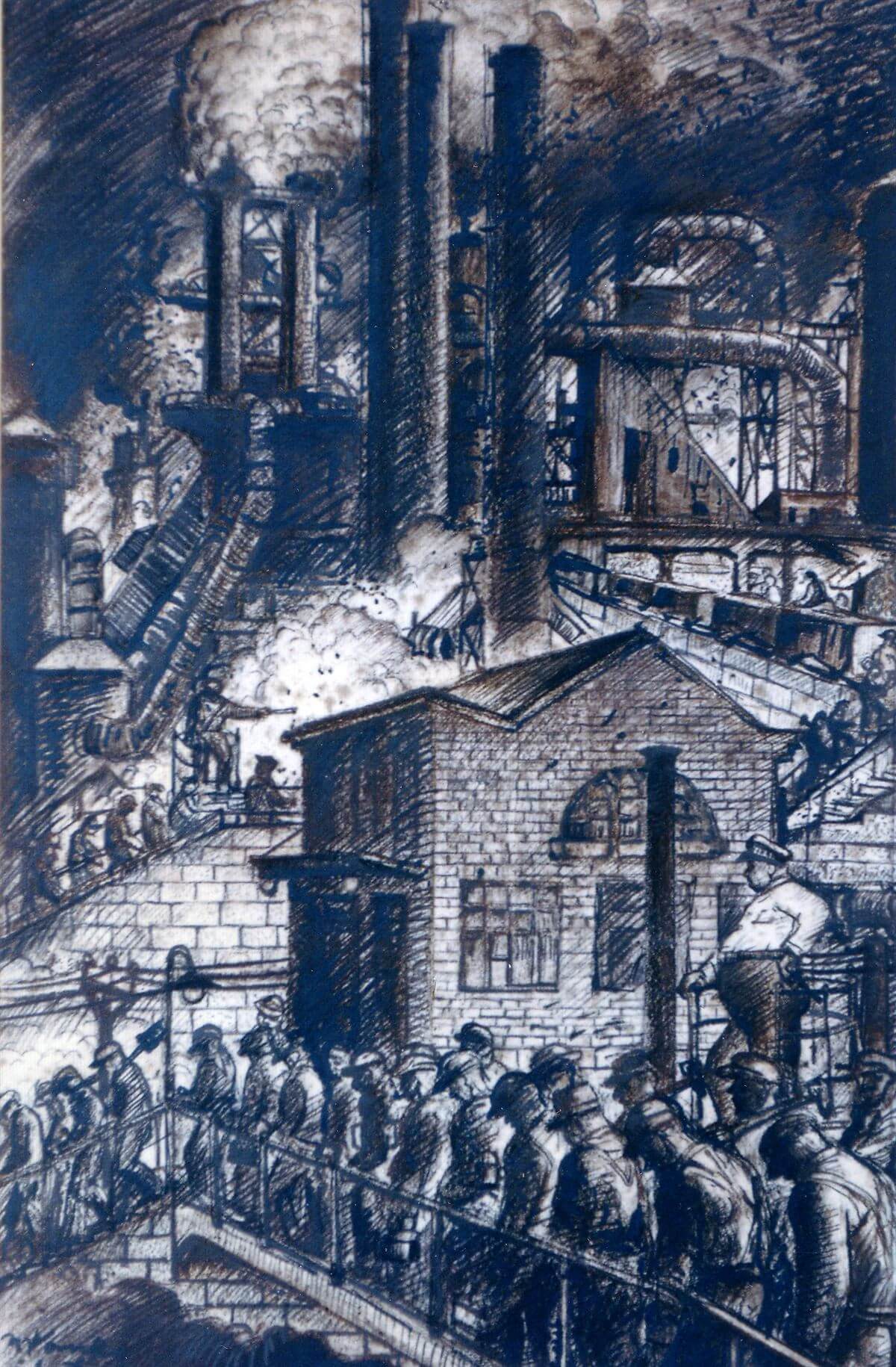

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, a whiff of Neorealism can be felt in Vanka's easel paintings. This is when a series of large compositions with scenes from a labourer’s life (Labourer, Sack Carrier, Farmers, Wounded Comrade, Rest) came into existence, predominantly embedded in an urban environment, and akin to the aesthetics of Critical Realism and the Neue Sachlichkeit. As in the case of a number of Vanka's concurrent portrait works, they are characterized by significantly more voluminous modelling of figures than it had beforehand been the case for him, and Vizner also pointed out their “frugal” palette. These works are not considered the artist's most outstanding accomplishments, and they are criticized for their theatricality, melodramatic decorativeness, drabness and vacuity.

During those years, however, Vanka resembles Babić, Becić and Miše, with whom he exhibited between 1926 and 1929 as part of the "Group of Four", which would be reflected with a significantly different understanding of colour in a series of his very successful Korčula landscapes from the early 30s, in which his intense colour palette is still alive, but at the same time it “imbibes the light more freely and is familiar with en-plein-air-esque sunshine” (Šimat Banov). The work Olive Trees (1934) from our Korčula collection exemplifies such works, in which critics usually praise the immediacy of the experience, the thoughtfulness and coherence of the composition, and the richness and careful orchestration of colours applied with visible brush strokes.

Two years after he entered the civil service, Vanka bought a house in Korčula, in Strečica Bay, where he allegedly regularly spent his summers gathering a, so to speak, colony of artists and intellectuals. Over time, he did the house (which he named Tusculum) up, amongst other things by executing a mural in his own design; he also planted a garden, where he placed some sculptures as well. That house had been destroyed in a fire even before Vanka left for America, purportedly at the hands of one of the locals revolted by the bohemian lifestyle of the peculiar crowd inhabiting it in the summer, but he soon restored it, although not to its former glory, and without the wall painting. Later on, in the 1930s, a summer house in Korčula (the relatively new villa Payer), which was built based on the project of the architect Branko Bon, was bought and refurbished by his wife's parents.

In the summer of 1926, while on a trip through Europe, the distinguished New York doctor DeWitt Stetten with his wife and daughter Margaret arrived in Zagreb at the invitation of an acquaintance, the lawyer Gustav Frank – whose portrait, made by none other than Vanka in 1918, is in the possession of the Zagreb National Museum of Modern Art. Vanka and the young American woman met and corresponded for years after that, until she arrived in Zagreb in the fall of 1930 determined to crown the relationship with marriage; hence, in August of the following year they got married in Lumbarda on Korčula. The very next year, their daughter Margaret, affectionately called Peggy, was born in Zagreb. During the same summer in Dubrovnik, the Vankas chanced upon the American writer, journalist and publicist Luj Adamič, who immigrated to the United States as a high school student, and his wife Stella. They spent a few weeks together in Vanka's house in Korčula, and thus the lifelong friendship of the two men began. Adamič described his encounter with Vanka in the book The Native's Return (1934). His life was a source of inspiration for an entire novel, and he also wrote about Vanka, dedicating an entire chapter to him, in the book My America (1938). Furthermore, after Vanka decided to continue his artistic work across the Atlantic, the Slovenian tried to provide him with commensurate publicity in his new homeland.

The Vankas arrived in the United States in September of 1934, initially not intending to settle there permanently. The painter prolonged the originally planned one-year absence by another year and finally resigned from his position as a result of “his departure in order to permanently settle in America”. Apart from the aforementioned dissatisfaction owing to the inability to procure an adequate professorial salary, the circumstances in the country, the political situation in Europe and the foreboding of the coming war, in addition to his wife's yearning to return to her homeland, all probably contributed to this. Vizner asserts that, although he would subsequently travel the world and thus stay in Europe, Vanka would visit Zagreb and Korčula only once more, in 1938, when he finally had the furniture transported from his Zagreb apartment across the ocean. It is worth, however, mentioning here the information from the archival fonds of the Korčula Port Authority that in March 1939, Margaret Vanka b. Stetten was granted a concession for the construction of a harbour, slipway and steps on public maritime property. According to some claims, the British diplomat Fitzroy Maclean was given lodging in the large villa during his secret diplomatic mission in the fall of 1943, and he allegedly described the experience in the third part of his memoir Eastern Approaches (1949). Based on his concise description, however, it is impossible to conclude with certainty whether the house in question really is the same house.

Vanka acquired the right of permanent residence and a work permit in the United States of America in 1937, and as early as three years later he was granted citizenship. The Vankas lived in New York for seven years, in luxurious apartments at prestigious addresses, rubbing elbows with the local elite. We learn something about this from the travel diary of Andrija Štampar, from the entry in which he describes the reception hosted by Dr. Stetten, a surgeon at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan: “On the first day, I was invited to a reception by Dr. Stetten, the father-in-law of the painter Vanka. There, in a luxurious apartment on Park Av., I encountered a large company, which, apart from me and Vanka, consisted only of Jews of all stripes and professions; there were also German refugees who had got into some American universities. Stetten explained to me that they were the best in their fields. [...] Among these people, Vanka looked out of place. Later, I visited Vanka in his apartment. There, he and his wife told me how they had been forced to marry each other. The little girl was constantly in my lap kissing me. Vanka complained to me that the child was actually lost to him, because she was being brought up in a completely different and to him completely foreign milieu. What hurt him the most was when she once told him that he had nothing to complain about at home because her mother was supporting him. Vanka often goes out to see the common people, how they live, because it seems that the immediate environment does not sit well with him.” The artist started working intensively very soon after arriving in his new environment. He wandered the streets of the metropolis, fascinated by its vertical vistas and imposing architecture. Thus, a whole series of pencil and sanguine drawings, along with watercolours with skyscraper motifs came into existence. He was equally fascinated by the industrial plants, steel mills and mines of western Pennsylvania and Ohio, which he discovered during his jaunts with Adamič during his first year in the new country. Vizner notes that this important facet of his early American artistic endeavours – depictions of monumental architecture and industry without the presence of a human figure (“only buildings, sky, dust, smoke”), is morally neutral because Vanka acts merely as an observer, which is completely different to the other key iconographic segment of that phase of his work – socially empathetic images of the urban poor and the underbelly of the city. A man of gentle nature, endowed with a rare trait that Adamič characterized as the Gift of Sympathy, this artist throughout his life showed a natural inclination for simple people, the poor, land workers and labourers, the economically and socially disadvantaged. In New York, which at that time had armies of the unemployed due to the consequences of the Great Depression, he documents the misery of entire impoverished families with pencil, sanguine, sepia and watercolour; visiting obscure and neglected parts of the megalopolis, he portrays wage earners, beggars, drunkards, petty criminals and prostitutes, and in Harlem the local, predominantly African American, population. He had a studio in a commercial building belonging to the Stettens not far from the notorious Bowery Street. According to the aforementioned art historian's opinion, with that part of his oeuvre, Vanka does not rely so much on his earlier experiences reminiscent of the New Reality; what was occurring was merely a knee-jerk reaction with which he “fitted quite naturally in with the trends of American social art of the thirties”, at a time when, after the dominance of various derivatives of modernism in the previous decade, influenced by difficult economic conditions, “realism once again became a prominent artistic direction”. These works are perhaps his most successful ones, and due to the fact that they received favourable critical reviews at Vanka's only more relevant New York exhibition, the one at the Newhouse Gallery in March 1939 – certainly the most outstanding part of his American creative period. Although the best-known examples of that phase are in the possession of the Doylestown Museum and some American private owners, some of the high-quality works, albeit without the New York vedutas with skyscrapers, were also donated to the Korčula Memorial Collection.

Vizner believes that the positive reception of that exhibition is partially due to the publicity received by the murals Vanka had executed two years earlier in the Franciscan Church of St. Nicholas of the local Catholic Parish of Croatian immigrant community in Millvale, a suburb of the industrial city of Pittsburgh. The commission of the then pastor Albert Žagar, which allowed Vanka a fair amount of artistic freedom, was actualised by the painter on three occasions: in the spring of 1937, during the summer and autumn of 1941 and, to a lesser extent, in 1951. In terms of form and content, the Millvale cycle is equally indebted to tradition and modernity. From its artistic expression, one can glean Vanka's knowledge of Byzantine icons, European old masters, modernism and avant-garde, as well as Mexican murals. He embedded elements of Croatian folklore and scenes from American everyday industrial life into established religious iconographic patterns, and he wove the condemnation of the atrocities of war and social inequality into the given subject-matter. Maroević, noting with the reservation that this imposing cycle was conceived as a kind of “Biblia pauperum” and is, therefore, perhaps justifiably too heavily rhetorically accented, assesses that it “appeals with certain iconographic solutions, a distinct humanistic message and the intention of affirming the socially and nationally frustrated participants of the American melting pot, and at the same time repels with its vehement poster-esque quality, exaggerated polarization and cartoonish definition of a number of actors (from capitalist profiteers to war combatants).”

The Korčula collection includes several artworks on paper/cardboard with a strong anti-war message, including the painting Camp, which shows in style and visual rhetoric some affinity with the oils from the first year of the war, which are actually (preparatory) versions of certain scenes from the Millvale church.

In the spring of 1941, the Vanka family moved to Rushland in eastern Pennsylvania. They settled on a farm in the idyllic rural setting of Bucks County, from which the major cultural centres, New York and Philadelphia, were relatively easily accessible, which is why it became home to a whole range of artists and intellectuals at the beginning of the 20th century. A rich cultural life developed in such an environment: art exhibitions, concerts, poetry nights, and amateur performances; consequently, Vanka exhibited relatively frequently as a member of local arts associations. He set up a studio in the outbuilding, and devoted himself intensively to landscaping the garden and growing flowers. He applies himself again to landscape painting, recording, especially in spring and autumn, the natural scenery not far from his estate, and he would remain devoted to this genre for the rest of his life. Vizner points out that these are feats of a simple composition, but a warm and fleshy palette, realized with short brush strokes, and, at times, with a painting trowel. In a peculiar way, these works continue the tradition of the dominance of colour of his South Dalmatian landscapes – Maroević, for example, believes that “the path towards an increasingly definite assimilation of van Gogh's palette and ductus would be unthinkable without Babić's mediation” – but with more frequent concessions to the shallow appeal bordering on sentimentality, which Šrepel objected to in some of his landscape paintings as early as the 1930s. Between 1948 and 1955, Vanka devoted himself anew to educational work, teaching a theoretical-practical introduction to art at a college in nearby Doylestown, only to ultimately resign in order to set off with his wife on a ten-month tour around East and South Asia, North Africa and Europe. In Asia, they visited Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia, Ceylon, and India. There the artist is drawn to unspoiled landscapes, local landmarks and customs, city scenes and the everyday life of the poor and marginalized, for instance an Indian leper colony. Vizner notes that this journey resulted in hundreds of sketches, drawings and pastels, which Vanka later used for larger compositions. The pastel Boats in Japan from the Korčula Collection is one such artwork, and the collection also includes the pastel Gulf of Mexico, of a slightly later date, created during one of Vanka's winterings in Mexico. The author of the dissertation remarks that the painter's Mexican landscapes, with a more subdued palette compared to, for example, those created in the vicinity of the White Bridge farm, are concordant with the “characteristics of an arid land”. It is worth mentioning that Mrs. Vanka also donated to the Academy's collection several unpretentious landscapes in chalk created during the artist's earlier trips across the United States. Maroević pointed out that Vanka's American landscape creations, be it the entries from Mexico, in which the artist “again pays the price for the attraction of exoticism”, or the landscapes of Bucks County, which “bring him back to his emotional, sentimental origins”, are undoubtedly inferior to his “veristic vedutas and socially coloured episodes from the American world”. A small number of allegorical-symbolist paintings also date from the Pennsylvania decades, which are a kind of continuation of the painter's preoccupations from his Brussels studies and his subsequent interwar mythological compositions, and are somewhat related to anti-war works from the the First World War period and the Millvale murals of the same subject-matter, but such works have not been represented in the Academy's Korčula collection. In the post-war period, Vanka devoted himself increasingly to sculpture and ceramics, but due to a small comparative sample, it is difficult to judge this segment of his creativity objectively.

***

Invoked earlier in the text, greater temperance in approaching some future evaluations of Vanka's oeuvre implies its necessary departure from the modernist paradigm of art history. Excluding to some extent Pintarić, and especially Vizner, in whose work we glimpse a different, but only vaguely indicated and insufficiently elaborated attitude, the previous critical and art historical reviews resonate with a formalist viewpoint with an inherent taxonomic meticulousness resulting in an unfavourable assessment of any deviation from the aesthetic norms, sequence of styles and desirable motif orientations. In accordance with the perspective that ignores or even disdains the propensity towards that which is content-related, the anecdotal, Vanka is rewarded only for works in which the primacy of vision and the immediacy of experience come to the fore. (Maroević: “Vanka is at his best when he is immediately motivated, that is, when he responds to the uniqueness of the challenge with the appropriateness of the means.”). More recent theoretical approaches, interdisciplinarity and other contemporary achievements in the field, which have already resulted in the revaluation of some authors’ works or simply a revival of interest in some forgotten artists, may, however, provide us with the key to re-examine Vanka's work. In the future, any more comprehensive review of his work would have to take into account the spatial-temporal context within which it was being created, both foreign and domestic. In addition to a detailed comparative analysis of his works scattered throughout public and private collections over two continents, it is indispensable to study archival material created by the agency of Vanka's artistic contemporaries and companions, especially their lesser-known and unpublished correspondence, which can contribute to a better understanding of the philosophical-aesthetic, social, and even the political atmosphere in which he created, as well as personal relationships that, at least in our country, more often than not had an effect on the developments on the art scene.

It has already been mentioned several times that Vanka is not easy to “place” within our art trends because of his stylistic distinctness. One possible way is to look at his participation in group exhibitions. For example, what piques interest is the painter's presence at the Exhibition of Croatian Artists in Osijek in 1916, which was the motive for the third split between the more conservative and the more progressive currents within the corpus of our modern art, as well as his preference for the “old” (Crnčić, Csikos, Frangeš-Mihanović, Jurkić, Iveković, Ferdo Kovačević and others), with a noticeable affinity of a number of his early works, especially some portraits, with the works of Miše (who, for example, was even thinking about a joint exhibition of the two the following year), Babić and other artists who exhibited as part of the renegade Spring Salon. In accordance with recent insights into the political motivation of the “secessionists”, supporters of the Yugoslav idea, it is possible that Vanka did not side with them due to differing political beliefs. However, it is difficult to pass judgement on this, because the current knowledge about the artist's life offers only a faint outline of the socio-political habitus, including its possible changes over time. Later he exhibited with the significantly more conservative Lada Association (in 1920, 1921, 1922), while at the same time some of his contemporary portrait works (for example, Self-Portrait and Portrait of Vladimir Lunaček) display more progressive features comparable to the contemporaneous portraits of Miše, Babić or Petar Dobrović. For example, Vanka was (in tandem with Csikos) dispatched to the French capital as a delegate of the “group of elder artists (of the Lada Association)” to organize The Yugoslav Exhibition in Paris in 1919, in which Croatian artists of all generations and political views took part. Resonating with the idea of searching for “our expression”, Vanka's interest in folk heritage in the second half of the 1920s resulted in a joint exhibition with Babić, Becić and Miše, which would, in turn, lead to significant changes in his expression. However, it remains unclear why he did not join them at exhibitions during the first half of the following decade. What is interesting at the same time is his noticeable stylistic duality: his landscapes from the early 1930s correspond in motif and style with the bourgeois “current” of searching for “our expression”, while at the same time, with his scenes from labourers' lives in the spirit of social/critical realism, he comes close to the ideas of the leftist Association of Artists “Zemlja”. Not formally belonging to any of these artistic collectives, while undoubtedly sharing some creative postulates of both, he rightfully found himself among the participants of The Exhibition of Zagreb Artists in 1934 with one landscape from the beginning of the decade, painted right before leaving for America, along with renegade members of the Zemlja association who had withdrawn after Krleža's Preface to Krsto Hegedušić's “Podravina Motifs” (Detoni, Postružnik, Tiljak, Augustinčić). The social component is also present in a series of his records from the everyday life of the New York poor created during the first years of his stay in that city. Art historian Ana Šeparović pointed out the similarity of that part of Vanka's oeuvre with Detoni's Paris cycle People from the Seine, published in the form of a graphic map upon his return to Croatia in 1934. This observation is very interesting if we compare, for example, Vanka's watercolour No More War (1935) from an American private collection – whose alleged immediate motif is one of the anti-war protests of the Popular Front, a left-wing organization influenced by the American Communist Party, and which Vizner, likening it to Ensor's work Christ's Entry Into Brussels, interpreted in the context of Vanka's pacifist beliefs – with Detoni's graphic artwork depicting the March of the Hungry, which undoubtedly served as his inspiration. This rough outline of the Croatian part of Vanka's artistic endeavour is merely an indication of the possible future directions of the research into his complex artistic oeuvre, a mere part of which is represented by the Academy's Korčula collection.