Strossmayer’s speech based on stenographic records was published in sections in contemporary newspapers. It was also presented in its entirety that same year in a separate publication and in Rad JAZU. Furthermore, Strossmayer’s bequest contains a fragmentary hand-written copy of the preparatory version of the speech.

Strossmayer began his lengthy expose by praising the Academy for its achievements in the field of science, highlighting in the process the unfavorable political and cramped financial circumstances in which those achievements were accomplished. He, therefore, considers it a just reason to “ascribe to our nation on the Balkan Peninsula a special affirmation, that it become what Tuscany is to beautiful Italy, a special kind of Athenaeum, a hearth and nursery for all our higher mental and moral aspirations and purposes”. He went on to thank Emperor and King Franz Joseph who, after the great earthquake hit Zagreb in 1880 and damaged the Palace of the Academy, generously aided its quick restoration. Emphasizing as beyond doubt the loyalty of the Croatian people to the ruling family, he called for the grace of God to protect them. He commends that same nation for the great austerity which it voluntarily undergoes for the greater good of creating “scientific and cultural institutions” and the Government that – with the condition of placing other institution under the Academy’s roof – participated in the cost of building its palace. Acknowledgement was also given to Zagreb’s executive and legislative government, as it surrendered “the most beautiful places” in cultural and educational institutions. Also, the government deserves credit as it, along with all “levels of the populace”, showed unwavering love and support to the patron from Đakovo as the embodiment of the most noble and enlightened desires, for over two days of festivities tied to the Academy. Strossmayer also thanked his “brother and old friend”, Rački, conscious of the great sacrifice that he had made in order to “raise, repair, finish, and decorate” the building which houses the Academy.

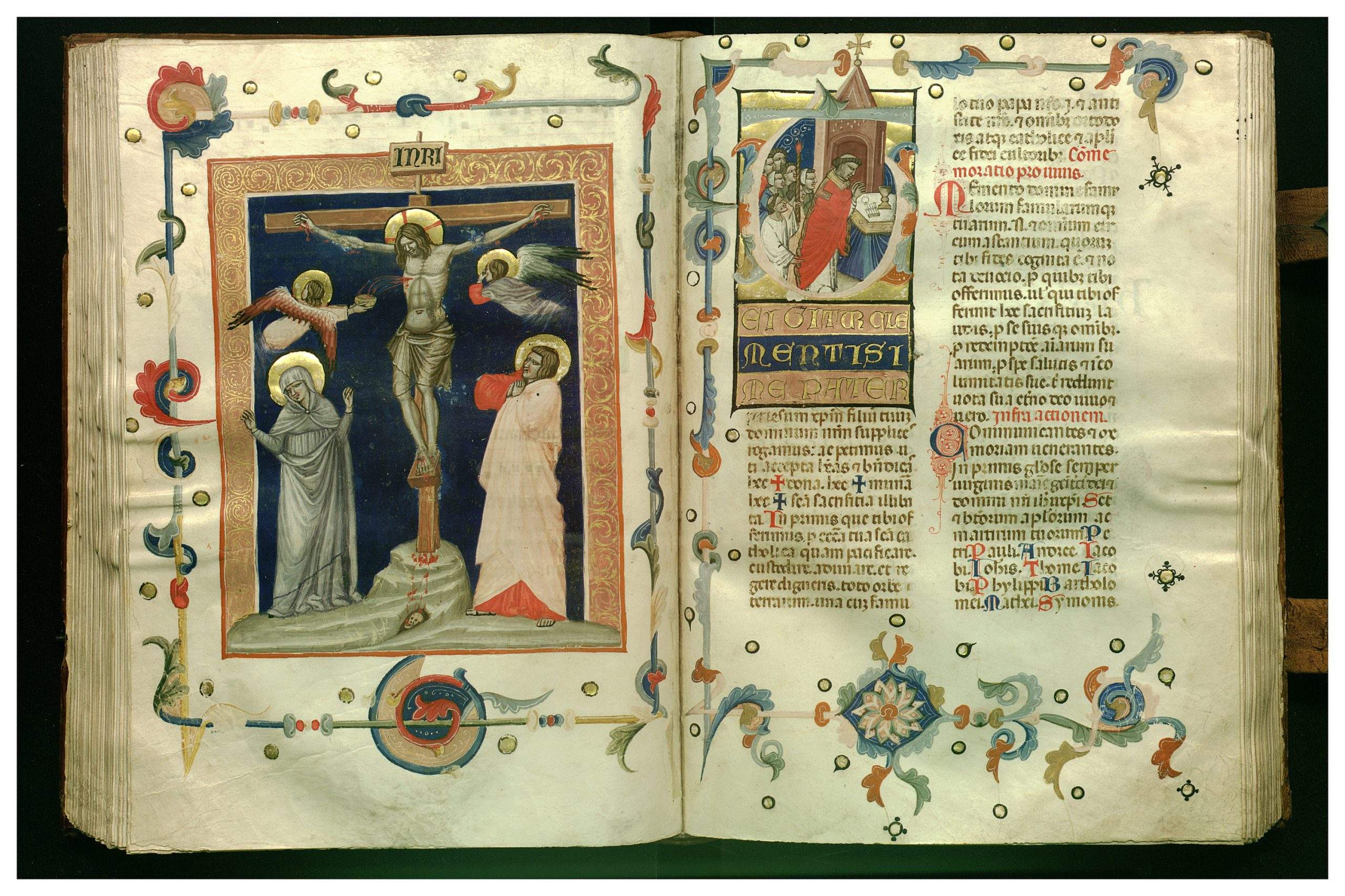

Strossmayer emphasizes that the Academy is celebrating two acquisitions with the ceremonial session. Firstly, the new representative headquarters that speaks to the glory and pride of the Academy itself, the City of Zagreb – as a successor of the famous Dubrovnik that was once the torchbearer of education and freedom – and the entire nation. Secondly, he names the collection of “paintings and artworks” that, after he had enjoyed it for the past thirty years, he gladly consigns to the Academy. He explained that with its scope and significance, the collection requires a specially dedicated building and care, and with it being in Zagreb, it is more accessible to the public and more useful than it would be in Đakovo. Guided by the same desire “that it be useful to the people and the learning youth”, the Bishop understood early on that he should collect painterly achievements that represent different schools of art. Therefore, he asked those gathered to allow him a brief presentation on the schools of art that are present in the collection, some of the more important examples of each, and on the motives that led him in his endeavors to found the Academy, the University, and the collection itself.

From his considerably extensive description of the collection, we can gauge Strossmayer’s artistic affinities and value judgements. He subsequently addressed the criticism that, instead of collecting artworks, the money could have been spent on everyday material needs of the poor, which the Bishop does not counter, but stresses that the poor do need addressing, without disregarding their spiritual and intellectual needs. According to Strossmayer’s understanding, cultural advancement is a guarantee for intellectual and every other kind of identity. Finally, as an argument for the existence of the collection he states the fact that it is definitely worth more now on the day of the Gallery’s opening than it was at the time when it was being formed. In more or less the same way he addressed the criticism that he neglected elementary and high school education in his patronage and put all efforts into high culture. To counter this, he gave convincing evidence. In the same spirit, he wished that the University would “fill up and heal”, until “all sciences are taught there in their organic form”, and that the Academy and University should preserve their autonomy. Finishing his speech, he addressed the objections that most of the gifted artworks are of a religious character: reasoning that, on the one hand, this is the spirit of the times in which they were created, and also underlining that – albeit from a very wide angle – medieval art is a reflection of a strong “religious emotion”, and on the other hand with the fact that he was, first and foremost, a priest. Therefore, he maintains that science and religion are inextricably linked, that they mutually support and complement each other, emphasizing that this same thought led him “in the founding of our great institutions”, and that it is thanks to the Academy and the University that they took the same path. He ardently asked that this should remain the same, proclaiming the Gallery open, and giving two medals, coined in memory of the Slavic pilgrimage to Rome in the year 1881, for its collection. These medals were a gift from the Pope who loved the Slavic people and promoted science, given as a sign of the eternal unity of science and faith.